Every September first I think of Jean Burden. This was her birthday – September Morn, she would say, and laugh. She was a poet, an essayist, a teacher, and a cat lover, and would have been one hundred eleven years old today. This photo is from one of her lovely Christmas parties, probably when she was in her seventies. She died at ninety three. I met Jean soon after moving to Altadena, when I mailed off a set of poems to the poetry editor of Yankee magazine. Yankee, published in New Hampshire, was always in our Long Island house when I was growing up, and deep in its back pages was a single page of really good, serious poetry. I had a poem about a blizzard that I thought was a good fit, but it was aiming high to hope to be published where famous poets trod. I sent it off with a few others and a self-addressed, stamped reply envelope – that’s how it was done before email and websites – and waited to hear back. I was surprised and delighted when it arrived with a letter accepting “The Blizzard,” and the amazing news that Yankee’s poetry editor lived in Altadena! She also invited me to be in her poetry workshop. And that’s how I met Jean Burden.

Jean was in her sixties and I wasn’t thirty yet. She was elegant, knowledgeable, confident, and lived in a wonderful small house that might have been part of a farm before the suburb filled in around it. Though I’d had a few poems published in places of no particular distinction, I had never read my poems aloud to anyone. I was nervous and self-conscious but she was gracious and kind, setting out cookies and tea for the group. She could be brutal about the poems themselves, but not to the poets. One of her favorite expressions when someone was devoted to a line, or an image, that didn’t work, was. “Cut it out. You can always use it in another poem.” We had fun applying this to random words and situations, but really it was good advice. She helped us back up and look at our poems more objectively, checking what we said against what we meant. Sometimes a poem surprised you as you wrote it.

My copies of her first book of poems, Naked as the Glass, and her second, Taking Light From Each Other, bloom with bookmarks for my favorite poems. The pet care books she wrote under the pen name Felicia Ames are still available in used editions. Cats were her thing, as they are mine; another bond. My copy of her anthology of cat poems, A Celebration of Cats, is tattered from use. I still have a stuffed toy cat from her collection that was given to me after she died.

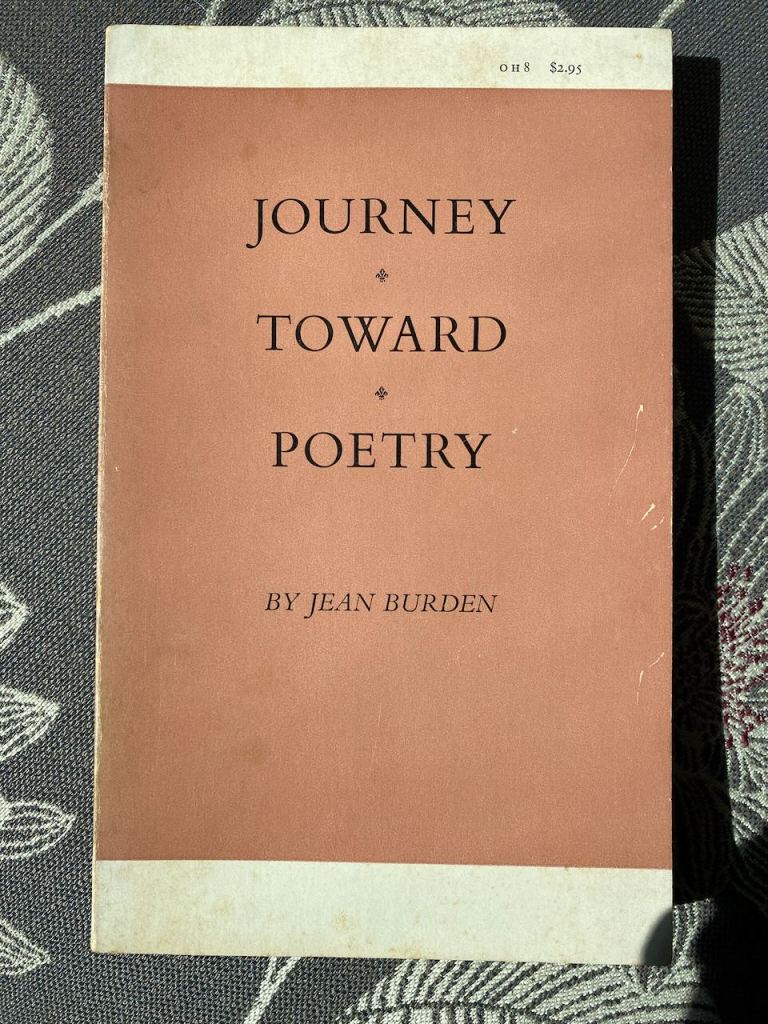

Her book Journey Toward Poetry is a good grounding in her approach. She says about her college studies with Thornton Wilder, that she was starved for “not only criticism, invaluable as this can be, but the contagion of enthusiasm for the art itself that can only be communicated by someone actively engaged in and committed to it.” Every year I got to meet, and sometimes have a seminar or dinner with, each wonderful poet invited to read at the Jean Burden Annual Poetry Series at Cal State LA. I felt the contagion of enthusiasm she wrote about, having Howard Nemerov advise me to take a line out of a poem, or even driving Maxine Kumin to the train station. Jean was long gone when her lovely little house was lost in the January fires, the porch where the cats sat, the small garden where they hunted, the rooms where poetry and laughter bounced off the walls. Whatever remained of it has been cleaned away, carted off to a landfill. It’s ready, now, for the next thing to happen there.